A Nightmare is Nothing but a Transfiguration

Written by Sama Moayeri

2020

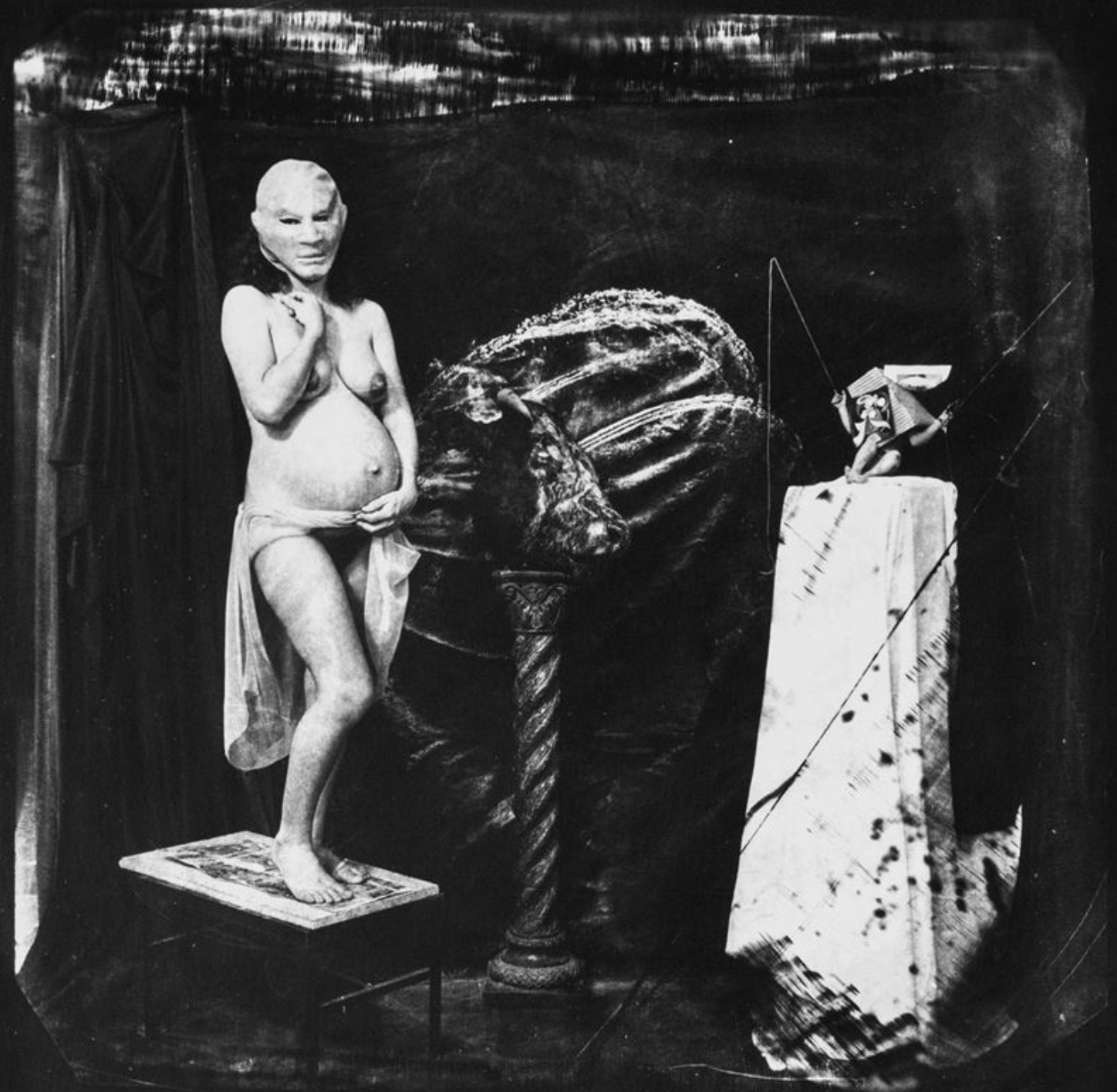

Joel Peter Witkin(1939) © Joel Peter Witkin

There is no violence more unforgivable than the violence that emerges from repression—not because it is excessive, but because its excess is inseparable from its genealogy. Every forbidden desire, denied gratification, every bodily impulse submerged beneath the polished surface of civility, does not vanish; it metastasizes, mutates, demanding expression in the form of rupture—an aesthetic of convulsion, what Artaud called "a body without refuge." In Joel-Peter Witkin’s photographs, this convulsive aesthetic reaches its logical extreme: bodies dismembered and restitched into new anatomical fictions, carcasses posed in tableaux that invoke both medieval reliquaries and butcher-shop vitrines, flesh reduced to the state Bataille called *the informe*—matter degraded until it reveals itself not as object, but as *base materialism*, organic detritus unredeemed by form. These photographs do not merely "represent" repression’s aftermath—they are the material evidence of repression’s productive force, the afterbirth of a society at war with its own bodily reality. The deformation Witkin offers is not aestheticized cruelty for its own sake; it is historical evidence—each mutilated body bears the trace of its cultural history. Post-war modernity, in its relentless pursuit of disembodiment—through mechanization, through the abstraction of labor, through the sanitization of public space—has made the body into both excess and taboo, something that must be hidden and yet obsessively returned to. To discuss post-war visual culture without invoking Picasso is almost impossible—but Witkin, particularly in his series *Mystery of Presence*, does not merely inherit Picasso’s language of fragmentation; he drags it out of the canvas and onto the slab, where paint becomes tissue, line becomes incision, and composition becomes vivisection. Witkin performs what Picasso could only suggest: the actual dismemberment of the human form. His terror lies not in the violence itself, but in its photographic mediation—the cold assertion that this flesh, these wounds, are real. The camera, that ultimate apparatus of the *indexical gaze*, renders every gash indisputable. In *Glass*, Witkin invokes mythology—but not as narrative, not as the symbolic inheritance of storytelling cultures. Instead, he reduces myth to its pictorial residue—the composite image left behind after centuries of visual reiteration. His Prometheus, his Daphne, his Cupid—they do not disturb because of Witkin’s compositional choices alone, but because they reawaken the foundational violence embedded in the myths themselves. This dismemberment of the human form, the fusion of eroticism and agony, is not Witkin’s invention—it belongs to a primordial visual grammar, one that has haunted the human imaginary since the first images were carved into cave walls. Witkin’s aesthetic can only be understood as a rupture within this continuum—a moment where the ancient violence of myth converges with the technological violence of photography. This is why Witkin’s images evade interpretation: they do not invite reflection, but demand submission. They are not illustrations, they are invocations. And yet, even here, Witkin’s relation to myth is not textual—it bypasses language entirely, engaging only with the image as it persists in the cultural unconscious. The myth is not told; it is shown. The image, stripped of narrative, becomes an autonomous wound. What appears nightmarish in Witkin’s work is not a product of artistic imagination, but the recombination of reality itself—a reality so fractured by repression and violence that its reassembly can only appear grotesque. These photographs are not "unreal"—they are hyperreal, so saturated with fact that they destabilize perception itself. And precisely because of this, they exhaust their own shock at first glance. Their power is the power of the jolt—instantaneous, exhilarating, but ephemeral. They are revolutions that burn out within a single gaze, satisfying the hunger for transgression but leaving no sediment behind. They do not haunt; they titillate. And so, the so-called courage Witkin claims—the audacity of excess—is, in the end, a gesture that addresses only the retina, not the mind. It operates at the level of stimulus, not thought. But a nightmare is never only what is seen; it is the process by which the seen is transformed by the seer, filtered through the private sediment of memory, desire, and fear. Witkin bypasses this process entirely. He delivers the transfigured image pre-digested, leaving no space for the viewer to perform the necessary alchemy of making the image their own. His violence remains his own—a private obsession projected into the public sphere. His representations of sexual and physical brutality are not invitations to confrontation, but acts of self-gratification, a theater of cruelty staged for the artist’s own gaze. In this, Witkin stands closer to the *auto-spectacle* of Artaud’s Theater of Cruelty than to any photographic tradition. His camera is not an eye; it is a scalpel. And like all solipsistic acts of cruelty, it ultimately consumes only itself.

Fair Use Notice: This website may contain copyrighted material used under the doctrine of Fair Use as outlined in Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. Such material is made available for the purposes of commentary, critique, education, and scholarly research. All images and texts remain the property of their respective copyright holders. No copyright infringement is intended. If you are the rights holder and believe your work has been used improperly, please contact us to request removal or proper attribution.