Tokyo After the Kiss

Written by Sama Moayeri

2020

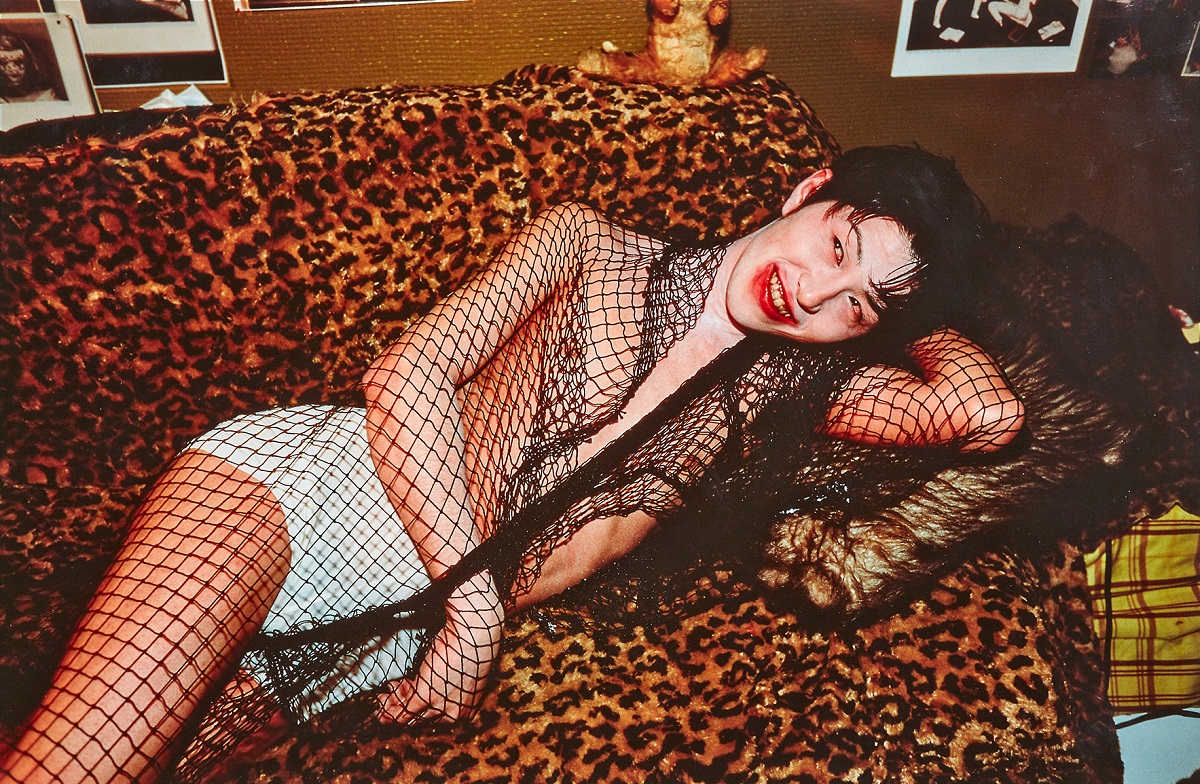

Nan Goldin, Takaho After Kissing, Tokyo, 1994 © 2016 Nan Goldin

A young man reclines on a leopard-print sofa, his body half-veiled in lace, a smudged smile stretched across his face—its curvature exaggerated to the point of parody, as though desire itself had curled at the edges. Nan Goldin’s photograph is not merely an image, but a declaration, an argument encoded in form: the overt articulation of sexual deviance as a visual grammar, its exposure demanding a confrontation with the concealed erotics of urban life. Tokyo, after the kiss, ceases to be a city. It becomes a scene. But what does it mean, in the late 20th and early 21st century, to display the sexual aberrant—not as pathological case study, not as transgressive icon, but as raw visual fact? And what is the moral economy of such disclosure? Two approaches invite themselves into this act of reading. The first operates at the level of the photograph’s immediate semantic surface—the arena of symbols, archetypes, cultural residues. The boy’s almond-shaped eyes, the vermillion smear encircling his mouth, evoke a visual lineage of the vampire: the mythological predator, erotically linked to consumption and contamination. Yet, this image does not rest on the Gothic alone. The leopard print sofa, an object thick with semiotic overdetermination (fetish object, pornography trope, sign of sexual labor), and the limp, almost anesthetized posture of his hand—all speak to the merging of pleasure and death drive, Eros and Thanatos locked in a decorative embrace. Within this constellation, violence simmers—not explicit, but residual, atmospheric, an undercurrent no less palpable for its discretion. Such violence, displaced from the arena of war photography but echoing its structure, shares with images of conflict an insistence on the body as both witness and evidence. Instinct, desire, and fear—perennial subjects of the lens—reappear here, reconstituted in velvet and lace. Goldin’s deliberate choice of subject, her unmistakable gaze that selects and arranges rather than discovers, dispels any fantasy of documentary neutrality. This is not a photograph taken from the world; it is a photograph made from a position. The act of exhibition—the decision to render public what could remain private—carries its own ideological charge. The question, then, is not whether Goldin records deviance, but to what end. Is the gesture an ethical demand—an appeal to confront the undercurrents of sexual economies—or does it function as an aesthetic normalization, dissolving deviance into style, into the image repertoire of contemporary taste? In a culture saturated by the visible, the very act of unveiling what is presumed hidden may already be obsolete. To show the unseen today is often only to confirm what is already tacitly known. Thus, Goldin’s deeper provocation lies not in revelation but in habituation—the slow training of the eye to see pleasure and violence not as exceptions, but as the texture of the everyday. This pedagogical impulse, far from confined to America, speaks to a globalized aesthetic order in which development and underdevelopment share the same visual codes. Violence, eroticism, spectacle: these are no longer local transgressions but global vernaculars. To normalize violence is not to condone it, but to embed it within the circuitry of recognition. And yet, history suggests that the dissemination of knowledge—or images—rarely coincides with ethical progress. The speed at which a phenomenon becomes visible consistently outpaces the emergence of any moral vocabulary capable of interpreting it. The second approach—both a contradiction and a complement to the first—engages a more latent semantic field, what Barthes might call the obtuse meaning. This reading acknowledges the image’s capacity to generate pleasure not despite, but through its violence. There is an illicit thrill in witnessing suffering unveiled—a transgressive sweetness in the disrobing of oppression. This is not simply the pleasure of voyeurism, but the pleasure of retribution: the erotic charge of watching a once-hidden violence turned back upon its source. The image becomes a trap, but not only for its subject. Takaho, wrapped in lace, is ensnared—but so is Goldin, bound to a system that demands her participation in the circulation of suffering. To photograph the wound is to both expose and prolong it. The viewer, too, becomes complicit: the image solicits shock, but this shock—repeated, iterated, aestheticized—quickly hardens into indifference. Each image erodes the next, until violence itself is reduced to an ambient hum. What remains is not just the image, but the apparatus—the cyclical production of visibility as both power and pleasure. In this sense, Goldin’s work participates in what it critiques: a machinery of visual domination that does not abolish the structures of power, but merely re-skins them. The beauty of power—its seductive sheen—is not incidental but essential. By rendering violence aesthetically legible, Goldin does not merely document it; she teaches us how to desire it. This is not a failure of the photograph, but a recognition of its limits: to expose power is not to abolish it. It is to submit to its logic and, in doing so, to prepare the eye for its next seduction.

Fair Use Notice: This website may contain copyrighted material used under the doctrine of Fair Use as outlined in Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. Such material is made available for the purposes of commentary, critique, education, and scholarly research. All images and texts remain the property of their respective copyright holders. No copyright infringement is intended. If you are the rights holder and believe your work has been used improperly, please contact us to request removal or proper attribution.